The following blog post, unless otherwise noted, was written by a member of Gamasutra’s community.

The thoughts and opinions expressed are those of the writer and not Gamasutra or its parent company.

We sat down with Beidi Guo, art director on the game, to discuss ups and downs of the development process, as well as the general fate of puzzle games.

Oleg Nesterenko, managing editor at GWO: Beidi, tell us about Lantern Studio.

There are four members on the team. There’s me. There’s Fox, who is our project manager. Susie Wang composed music for the game, and Wang Guan is our programmer. We are scattered around the world. We are based in London, Toronto, and Shanghai. We mostly keep in touch on Skype.

Susie and I are also in charge of social media, as well as reporting to our Kickstarter backers.

We try to do everything ourselves to save budget. But towards the end of the development, we hired our current marketing manager George Eastmead from Acorngames, who helped us manage our accounts on Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, Discord. For example, he also suggested cross-promotion with other teams. We have met a lot of other indie developers over these years, so when their games launch, we will RT for each other, or post some fan art featuring our characters but using their game style.

Limited budget means that you have to be very selective about game conventions that you attend.

In the beginning, we tried to attend conventions that were free. Also there are organizations that help indie teams in the UK, like an organization called Tentacle Zone. They help indie developers hire space at big conventions like EGX Rezzed and Insomnia. They have a dedicated zone there called Tentacle Zone, and usually they offer indie developers booths and equipment.

Later, we signed with our publishers. They helped us promote our game at trade shows like GDC and Gamescom.

Good for you. But you weren’t quite as smart about your Kickstarter campaign, right? The money you raised only lasted you one year, and it took another three years to finish the game. How did that happen?

We lacked experience. We thought we could finish the game in one year. A year and a half, tops. But after we started the development, we realized that this game had way more potential than we anticipated. We had to decide whether to keep the game small so we could finish it within our budget or to try to get the game done the way we actually wanted. And this was probably two, three times larger than our original plan.

We didn’t want to give up. All of us dipped into our savings and chipped in. This was enough to last us for another three years.

It was not an easy decision. We also had to apologize to our Kickstarter backers that this game was taking way longer than we promised. But our backers are very patient. Instead of rushing us, they agreed to wait for us to deliver a more complete experience, they have always shown us support and love, which was incredible.

And you didn’t want funding from your publishers?

We only signed with them in 2018, when most of the game was ready.

Before that, however, in 2017, a few individual investors had approached us to say they would like to invest in our game, but we turned that down. We wanted to keep our creative freedom in making LUNA.

If publishers offer funding, that often means they might interfere with your creative decisions. In certain cases, devs even sell their IP to their publisher, which is something we definitely don’t recommend. If you don’t own your game, what’s the point of being indie?

That must have been some pretty dark times, risking your own money, not knowing exactly what to do with your game…

It was tough, but at least we could do something about it. The hardest times were when unpredictable situations happened that were completely out of our control.

For example, when we needed to publish our game in China. By the lastest regulation, you need to apply for a license. We had to queue a year early because we knew it was going to take a while, but we didn’t know how long exactly. Throughout the whole process, there is no way you can check with the staff in the relevant department. Ask them “How’s it going? Is there any extra document we need to supply?” The communication is strictly one-sided. If they find a problem, they will get back to you and ask you to fix it. Then you have to re-submit which was really time consuming.

We never expected this because the law only came into force in early 2018. And we definitely wanted to publish our game in China. We are a Chinese team, and a lot of Chinese players supported us. No way we could let them down.

This was probably the hardest time. I mean you want to start to market your game almost half a year before you launch it. But without knowing when we were getting this license, we couldn’t really start any promotion. And we didn’t want to promote our game too early. If you promote for too long, people can get tired of waiting. This caused us lots of anxiety on top of the existing health problems. There was literally nothing we could do but wait and pray.

Eventually we got the license after nine months.

Health problems, you said?

It is a common problem among all indies, when you don’t have enough budget to afford a healthy lifestyle. No extra money to spend on gym or eating healthy. And you are working from home, so it’s kind of lonely as well.

And we tried not to take any time off because we were already way behind our original schedule. Towards the end of the development, it started taking a toll on the health of some of our team members. We were burnt out. It felt like all creativity was squeezed out of us. We looked at our game, and all we could see was bugs.

Last year, while we were still waiting for that license, the whole team decided to take a couple of weeks off so we could recover from this burnout.

Pray and take breaks. Essential advice for all indies out there. Let’s talk about the game itself. How did you come up with an idea for LUNA?

The general philosophy behind the game was inspired by the Earthsea series written by Ursula K. Le Guin. Her novels are never one-dimensional, it’s not just the hero versus evil, the light versus the dark side. She emphasizes how everything is interconnected. Without shadow, there will be no light, and vice versa. It’s something we don’t really see in the majority of games nowadays.

Which is why there is no evil in LUNA. There are no boss fights. It’s more about a balance. The more light you create, the more shadow will follow. One’s ambition of becoming the best and doing the good deeds can also cause devastating consequences.

How did you design the puzzles?

In the beginning of the development, we just brainstormed for a couple of weeks. We created a folder called “Crazy Ideas.” And we threw in all kinds of ideas, whether it was on mechanics, visuals or the story. At this stage, we didn’t even think if these ideas could get us anywhere.

When we run out of ideas, we all sat down to mix and match different concepts. For example, we have a room with a lot of objects lying around. So it might be fun to introduce a gameplay where people need loads of stuff to interact with.

Or the other way around. For example, we came up with this mechanic that we really liked. You know, when the character can turn into a shadow. So we think, okay, what setting is suitable for this kind of gameplay? Probably you need a room with walls. It can’t happen outdoors. And to emphasize the contrast between light and dark, this room needs a very strong light source. So you can have lots of candles. That’s how we came with an idea of a room for this puzzle.

We just tried to fill each room with the suitable mechanic and gameplay. But all of this changed throughout the development. For some of the rooms we couldn’t figure out the right mechanic. Or we started developing and then realized that it wasn’t as fun as we thought or it had nothing to do with our story.

Then we gave up some of the levels that were already in development. We also got rid of ideas that were technically too challenging for us.

Did you playtest your puzzles?

Feedback from players is crucial. The four of us, we think very much alike and sometimes we can’t help but develop this sort of tunnel vision, stuck in our own judgement. Therefore, whenever we finished a level, we tried to invite as many people as we could to test it.

First of all, we would invite our game designer friends from the industry. They are professionals so they would give us feedback from a design point of view. After that, when we fixed some of the gameplay issues, we would give it to more casual players.

That included our friends, our families, who don’t even play games. But we like to know what their first impression is. Because sometimes when we thought a puzzle was easy but we found a lot of people got stuck. We need to ask them for feedback. We want to know their way of approaching the puzzles, was the hint not visible enough, or is there a confusion about the UI design? Then we have to fix these issues.

That’s another important reason for us to go to game conventions. You embrace hundreds of players. You can stand behind them, watch them, see exactly how they interact with a level. And then you talk to them. That’s how we collect data.

According to feedback from players, we constantly fine-tune one aspect or another. Some levels have been developed very smoothly, others went through multiple iterations.

You can’t test them forever though. When do you know that a level is complete?

Once you have around 50 or 30 people giving you the same feedback, it’s safe to say that we know how most of the audience is gonna react toward this level. However, there will always be players that think differently, we just have to embrace that.

Getting individual puzzles right is hard enough, but you also have to think about their place on a difficulty curve.

A good learning curve is difficult to nail. This is something we also test on players. We did a lot of fine-tuning at the later stage changing the order of certain puzzles to see which sequence works the best.

We discovered, for example, that the difficulty should be uneven towards the end. If players have been playing a game for hours, puzzles of the same difficulty might seem more difficult because people are just tired. So we need to throw in one or two levels in between that are relatively easy to give them some time to recover, to just enjoy the story and the environment.

After all this fine-tuning, are there any weaknesses in LUNA that you can think of?

Perhaps we tried too hard to be original. This is why sometimes we made our puzzles too different from each other. One of the common pieces of feedback that we received is that there is not enough continuity between puzzles. You learn a skill in the beginning of the game but then you have to wait for a very long time to use that ability again. We might be able to improve that in the future.

We also tried too hard to appeal to a broad audience. I wish we had understood earlier who our core audience was. If we had communicated with them more, probably we could have avoided some easy but less interesting puzzles that just tried to make sure everyone can pass the early stage of the game.

I mean, this is our first game. We were not that confident about our decisions sometimes. In hindsight, I would say that for an indie team it’s ok to make a game the general public will criticize as long as your key audience really likes it. They will tell their friends about your game, and that’s how you slowly reach the audience that you are aiming for. You might not be able to find it right away because it’s a niche market, and there are always risks involved when you do something new. People are usually more comfortable with the things they are used to, I guess.

Do you now have a better idea of who your target audience is?

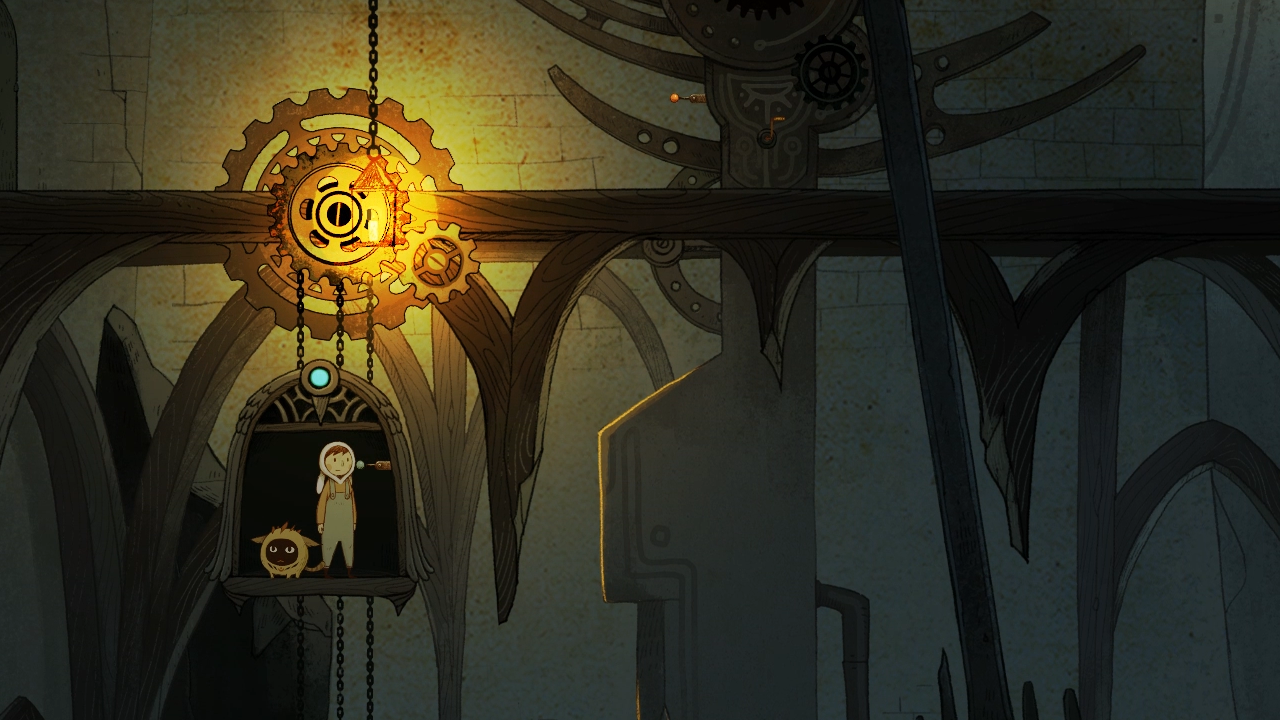

It’s people who like to take their time and enjoy every detail in the game. Whenever they finish a puzzle, they don’t just rush to the next level so they can beat the whole game in two hours. They like to linger around and look at those paintings and try to use their imagination to figure out the lore, the background story.

Many people found them somewhat obscure. Did you devise them that way to encourage players to slow down when playing the game?

We definitely didn’t want to confuse people. We tried to make the story understandable by the majority of people. We tried to use the universal cinematic language. For flashbacks, for example, we used a different tone so people understand that this bit happened in the past. Or, another example, in so many cartoons and tv shows, whenever you hear a harp playing, you know that this is some memory from the past. This is the kind of cinematic language we tried in our game.

Sometimes, though, it’s ok to leave it up to the player to figure things out for themselves. I trust players. They chose to play a puzzle game without a single line of dialogue, that means they have certain expectations about being challenged, they have certain expectations about themselves and are able to figure things out.

So yes, it’s about how you play it.

A lot of the lore of the story is embedded in individual rooms. Once you have completed enough of the game, you also realize that the whole tower actually is a place designed for a few people to live there. There are kitchens, there are bedrooms. They are not just random stage props. If you start to wonder who actually lives there, which bedroom is connected with which character based on the decorations in the background, you might figure out what kind of relationship there is between these characters.

Was it even worth it? Inventing all this rich narrative that might be completely lost on players who just want to beat the game?

Absolutely. People do not typically replay puzzle games. But what we saw with LUNA is that many players return to the game because they didn’t get every single detail at their first go. They don’t replay it for the sake of puzzles. They just want to get the full picture of the story.

For these players, we even designed some Easter eggs.

For example, one of the cutscenes cannot be activated in the first round. You will see it still locked in the gallery. We hope this will encourage people to wonder if they have missed something.

You need to revisit some locations and rethink your previous assumptions to unlock this extra bit of the story.

We’ve also designed a LUNA language which is decodable. Amazingly, many people decoded it in the first 24 hours. So if you know how to decode it, you can actually go back to the game and read those writings in books, in paintings on the wall. That’s something that a lot of YouTubers did on their streams.We’re really happy to see players willing to spend so much time in doing this.

Unlocking all these secrets will answer some of the questions, but probably raise some new ones. We hope that people who are really interested in the setting of the world will then move from the game to our website because we keep a very detailed devlog and we made some interviews that explain the lore behind the story. Also we have a lot of behind the scene design process, sketches and images included in our digital artbook, which is also available on Steam.

So it was an artistic decision to not use any real language in the game?

It was both a pragmatic and a creative decision.

Sometimes when I play a game which is dialogue heavy, I switch between English and Chinese. More often than not, a lot of jokes, a lot of puns get lost in the translation. It was really a shame but I also understood translating these is very difficult. So even if you localize your game, some meaning will still get lost in translation.

However, we can all understand emotions by looking at characters’ facial expressions and movement. It is the universal language we all share. Like one of my favorites, Oscar-winning animated film The House of Small Cubes by Kunio Kato, and Arrival, a picture-only graphic novel by Australian artist Shaun Tan. None of these two works has dialogue yet I can still be moved by them deeply.

Last but not least, as a small team we have a very limited budget, and writing dialogue is also not our biggest strength. So making a game that doesn’t need any localization was definitely a better choice for us.

What’s next for Lantern Studio?

I don’t know, to be honest. I never expected LUNA to become such a huge project. If, in the future, we have an idea, a story we absolutely adore and we feel like we have to tell it, we’ll make another game. That is, if a game is the right medium for this idea. If, for example, a graphic novel is a more suitable format for it, then we’ll do a graphic novel. Or an animated short film.

The things we’ve learned as game developers, they are not going to go away, even if we don’t apply them to game design. First and foremost, we have learned to solve problems. These skills can be used in software engineering, animation, etc. Who knows? Maybe in the future there will be no computers as we know them, and completely new media will emerge.

Congratulations on the adventure that is LUNA and good luck in the future, computer-free or not!

The thoughts and opinions expressed are those of the writer and not Gamasutra or its parent company.

This interview was originally published on Game World Observer on March 24, 2020.

LUNA The Shadow Dust is

a hand-animated point-and-click puzzle adventure that came out on

February 13. It is the debut title of the Chinese team called Lantern Studio.We sat down with Beidi Guo, art director on the game, to discuss ups and downs of the development process, as well as the general fate of puzzle games.

One of the two is Beidi Guo, Art Director

There are four members on the team. There’s me. There’s Fox, who is our project manager. Susie Wang composed music for the game, and Wang Guan is our programmer. We are scattered around the world. We are based in London, Toronto, and Shanghai. We mostly keep in touch on Skype.

Susie and I are also in charge of social media, as well as reporting to our Kickstarter backers.

We try to do everything ourselves to save budget. But towards the end of the development, we hired our current marketing manager George Eastmead from Acorngames, who helped us manage our accounts on Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, Discord. For example, he also suggested cross-promotion with other teams. We have met a lot of other indie developers over these years, so when their games launch, we will RT for each other, or post some fan art featuring our characters but using their game style.

A rare moment of Lantern Studio being physically together

In the beginning, we tried to attend conventions that were free. Also there are organizations that help indie teams in the UK, like an organization called Tentacle Zone. They help indie developers hire space at big conventions like EGX Rezzed and Insomnia. They have a dedicated zone there called Tentacle Zone, and usually they offer indie developers booths and equipment.

Later, we signed with our publishers. They helped us promote our game at trade shows like GDC and Gamescom.

Good for you. But you weren’t quite as smart about your Kickstarter campaign, right? The money you raised only lasted you one year, and it took another three years to finish the game. How did that happen?

We lacked experience. We thought we could finish the game in one year. A year and a half, tops. But after we started the development, we realized that this game had way more potential than we anticipated. We had to decide whether to keep the game small so we could finish it within our budget or to try to get the game done the way we actually wanted. And this was probably two, three times larger than our original plan.

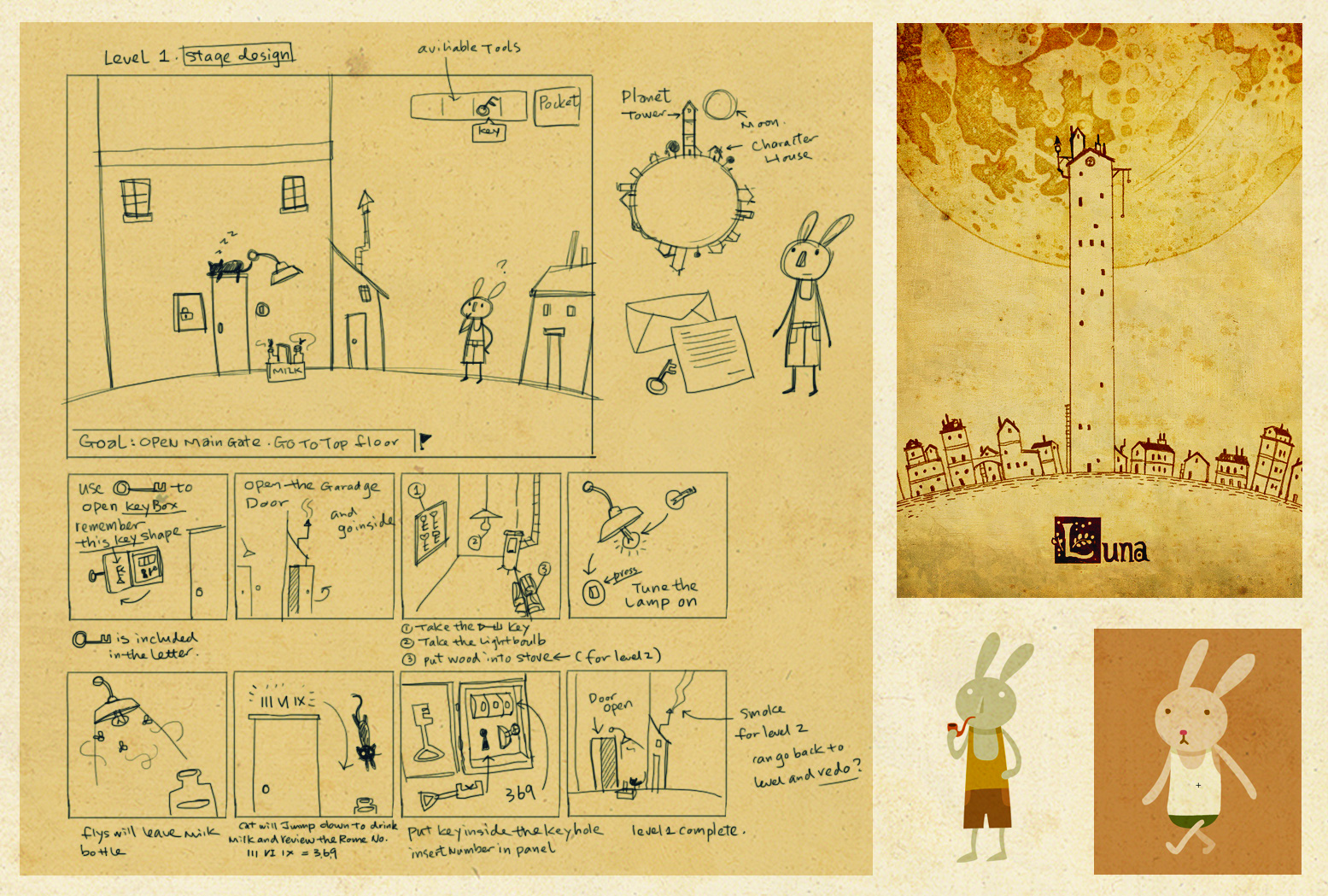

Beidi’s very first concept art for LUNA, when it was still a very small game that only existed in her head

It was not an easy decision. We also had to apologize to our Kickstarter backers that this game was taking way longer than we promised. But our backers are very patient. Instead of rushing us, they agreed to wait for us to deliver a more complete experience, they have always shown us support and love, which was incredible.

And you didn’t want funding from your publishers?

We only signed with them in 2018, when most of the game was ready.

Before that, however, in 2017, a few individual investors had approached us to say they would like to invest in our game, but we turned that down. We wanted to keep our creative freedom in making LUNA.

If publishers offer funding, that often means they might interfere with your creative decisions. In certain cases, devs even sell their IP to their publisher, which is something we definitely don’t recommend. If you don’t own your game, what’s the point of being indie?

That must have been some pretty dark times, risking your own money, not knowing exactly what to do with your game…

It was tough, but at least we could do something about it. The hardest times were when unpredictable situations happened that were completely out of our control.

For example, when we needed to publish our game in China. By the lastest regulation, you need to apply for a license. We had to queue a year early because we knew it was going to take a while, but we didn’t know how long exactly. Throughout the whole process, there is no way you can check with the staff in the relevant department. Ask them “How’s it going? Is there any extra document we need to supply?” The communication is strictly one-sided. If they find a problem, they will get back to you and ask you to fix it. Then you have to re-submit which was really time consuming.

We never expected this because the law only came into force in early 2018. And we definitely wanted to publish our game in China. We are a Chinese team, and a lot of Chinese players supported us. No way we could let them down.

This was probably the hardest time. I mean you want to start to market your game almost half a year before you launch it. But without knowing when we were getting this license, we couldn’t really start any promotion. And we didn’t want to promote our game too early. If you promote for too long, people can get tired of waiting. This caused us lots of anxiety on top of the existing health problems. There was literally nothing we could do but wait and pray.

Eventually we got the license after nine months.

Health problems, you said?

It is a common problem among all indies, when you don’t have enough budget to afford a healthy lifestyle. No extra money to spend on gym or eating healthy. And you are working from home, so it’s kind of lonely as well.

And we tried not to take any time off because we were already way behind our original schedule. Towards the end of the development, it started taking a toll on the health of some of our team members. We were burnt out. It felt like all creativity was squeezed out of us. We looked at our game, and all we could see was bugs.

Last year, while we were still waiting for that license, the whole team decided to take a couple of weeks off so we could recover from this burnout.

Pray and take breaks. Essential advice for all indies out there. Let’s talk about the game itself. How did you come up with an idea for LUNA?

The general philosophy behind the game was inspired by the Earthsea series written by Ursula K. Le Guin. Her novels are never one-dimensional, it’s not just the hero versus evil, the light versus the dark side. She emphasizes how everything is interconnected. Without shadow, there will be no light, and vice versa. It’s something we don’t really see in the majority of games nowadays.

Which is why there is no evil in LUNA. There are no boss fights. It’s more about a balance. The more light you create, the more shadow will follow. One’s ambition of becoming the best and doing the good deeds can also cause devastating consequences.

How did you design the puzzles?

In the beginning of the development, we just brainstormed for a couple of weeks. We created a folder called “Crazy Ideas.” And we threw in all kinds of ideas, whether it was on mechanics, visuals or the story. At this stage, we didn’t even think if these ideas could get us anywhere.

When we run out of ideas, we all sat down to mix and match different concepts. For example, we have a room with a lot of objects lying around. So it might be fun to introduce a gameplay where people need loads of stuff to interact with.

Or the other way around. For example, we came up with this mechanic that we really liked. You know, when the character can turn into a shadow. So we think, okay, what setting is suitable for this kind of gameplay? Probably you need a room with walls. It can’t happen outdoors. And to emphasize the contrast between light and dark, this room needs a very strong light source. So you can have lots of candles. That’s how we came with an idea of a room for this puzzle.

We just tried to fill each room with the suitable mechanic and gameplay. But all of this changed throughout the development. For some of the rooms we couldn’t figure out the right mechanic. Or we started developing and then realized that it wasn’t as fun as we thought or it had nothing to do with our story.

Then we gave up some of the levels that were already in development. We also got rid of ideas that were technically too challenging for us.

Did you playtest your puzzles?

Feedback from players is crucial. The four of us, we think very much alike and sometimes we can’t help but develop this sort of tunnel vision, stuck in our own judgement. Therefore, whenever we finished a level, we tried to invite as many people as we could to test it.

First of all, we would invite our game designer friends from the industry. They are professionals so they would give us feedback from a design point of view. After that, when we fixed some of the gameplay issues, we would give it to more casual players.

That included our friends, our families, who don’t even play games. But we like to know what their first impression is. Because sometimes when we thought a puzzle was easy but we found a lot of people got stuck. We need to ask them for feedback. We want to know their way of approaching the puzzles, was the hint not visible enough, or is there a confusion about the UI design? Then we have to fix these issues.

That’s another important reason for us to go to game conventions. You embrace hundreds of players. You can stand behind them, watch them, see exactly how they interact with a level. And then you talk to them. That’s how we collect data.

According to feedback from players, we constantly fine-tune one aspect or another. Some levels have been developed very smoothly, others went through multiple iterations.

You can’t test them forever though. When do you know that a level is complete?

Once you have around 50 or 30 people giving you the same feedback, it’s safe to say that we know how most of the audience is gonna react toward this level. However, there will always be players that think differently, we just have to embrace that.

Getting individual puzzles right is hard enough, but you also have to think about their place on a difficulty curve.

A good learning curve is difficult to nail. This is something we also test on players. We did a lot of fine-tuning at the later stage changing the order of certain puzzles to see which sequence works the best.

We discovered, for example, that the difficulty should be uneven towards the end. If players have been playing a game for hours, puzzles of the same difficulty might seem more difficult because people are just tired. So we need to throw in one or two levels in between that are relatively easy to give them some time to recover, to just enjoy the story and the environment.

After all this fine-tuning, are there any weaknesses in LUNA that you can think of?

Perhaps we tried too hard to be original. This is why sometimes we made our puzzles too different from each other. One of the common pieces of feedback that we received is that there is not enough continuity between puzzles. You learn a skill in the beginning of the game but then you have to wait for a very long time to use that ability again. We might be able to improve that in the future.

We also tried too hard to appeal to a broad audience. I wish we had understood earlier who our core audience was. If we had communicated with them more, probably we could have avoided some easy but less interesting puzzles that just tried to make sure everyone can pass the early stage of the game.

I mean, this is our first game. We were not that confident about our decisions sometimes. In hindsight, I would say that for an indie team it’s ok to make a game the general public will criticize as long as your key audience really likes it. They will tell their friends about your game, and that’s how you slowly reach the audience that you are aiming for. You might not be able to find it right away because it’s a niche market, and there are always risks involved when you do something new. People are usually more comfortable with the things they are used to, I guess.

Do you now have a better idea of who your target audience is?

It’s people who like to take their time and enjoy every detail in the game. Whenever they finish a puzzle, they don’t just rush to the next level so they can beat the whole game in two hours. They like to linger around and look at those paintings and try to use their imagination to figure out the lore, the background story.

Many people found them somewhat obscure. Did you devise them that way to encourage players to slow down when playing the game?

We definitely didn’t want to confuse people. We tried to make the story understandable by the majority of people. We tried to use the universal cinematic language. For flashbacks, for example, we used a different tone so people understand that this bit happened in the past. Or, another example, in so many cartoons and tv shows, whenever you hear a harp playing, you know that this is some memory from the past. This is the kind of cinematic language we tried in our game.

Sometimes, though, it’s ok to leave it up to the player to figure things out for themselves. I trust players. They chose to play a puzzle game without a single line of dialogue, that means they have certain expectations about being challenged, they have certain expectations about themselves and are able to figure things out.

So yes, it’s about how you play it.

A lot of the lore of the story is embedded in individual rooms. Once you have completed enough of the game, you also realize that the whole tower actually is a place designed for a few people to live there. There are kitchens, there are bedrooms. They are not just random stage props. If you start to wonder who actually lives there, which bedroom is connected with which character based on the decorations in the background, you might figure out what kind of relationship there is between these characters.

Was it even worth it? Inventing all this rich narrative that might be completely lost on players who just want to beat the game?

Absolutely. People do not typically replay puzzle games. But what we saw with LUNA is that many players return to the game because they didn’t get every single detail at their first go. They don’t replay it for the sake of puzzles. They just want to get the full picture of the story.

For these players, we even designed some Easter eggs.

For example, one of the cutscenes cannot be activated in the first round. You will see it still locked in the gallery. We hope this will encourage people to wonder if they have missed something.

You need to revisit some locations and rethink your previous assumptions to unlock this extra bit of the story.

We’ve also designed a LUNA language which is decodable. Amazingly, many people decoded it in the first 24 hours. So if you know how to decode it, you can actually go back to the game and read those writings in books, in paintings on the wall. That’s something that a lot of YouTubers did on their streams.We’re really happy to see players willing to spend so much time in doing this.

Unlocking all these secrets will answer some of the questions, but probably raise some new ones. We hope that people who are really interested in the setting of the world will then move from the game to our website because we keep a very detailed devlog and we made some interviews that explain the lore behind the story. Also we have a lot of behind the scene design process, sketches and images included in our digital artbook, which is also available on Steam.

So it was an artistic decision to not use any real language in the game?

It was both a pragmatic and a creative decision.

Sometimes when I play a game which is dialogue heavy, I switch between English and Chinese. More often than not, a lot of jokes, a lot of puns get lost in the translation. It was really a shame but I also understood translating these is very difficult. So even if you localize your game, some meaning will still get lost in translation.

However, we can all understand emotions by looking at characters’ facial expressions and movement. It is the universal language we all share. Like one of my favorites, Oscar-winning animated film The House of Small Cubes by Kunio Kato, and Arrival, a picture-only graphic novel by Australian artist Shaun Tan. None of these two works has dialogue yet I can still be moved by them deeply.

Last but not least, as a small team we have a very limited budget, and writing dialogue is also not our biggest strength. So making a game that doesn’t need any localization was definitely a better choice for us.

What’s next for Lantern Studio?

I don’t know, to be honest. I never expected LUNA to become such a huge project. If, in the future, we have an idea, a story we absolutely adore and we feel like we have to tell it, we’ll make another game. That is, if a game is the right medium for this idea. If, for example, a graphic novel is a more suitable format for it, then we’ll do a graphic novel. Or an animated short film.

The things we’ve learned as game developers, they are not going to go away, even if we don’t apply them to game design. First and foremost, we have learned to solve problems. These skills can be used in software engineering, animation, etc. Who knows? Maybe in the future there will be no computers as we know them, and completely new media will emerge.

Congratulations on the adventure that is LUNA and good luck in the future, computer-free or not!

This interview was originally published on Game World Observer on March 24, 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment